How Facebook Makes Sense of Fragmented Communities for Transient People

Three years ago, I introduced two of my best friends who both work for the city of Charlotte. My friend from UNCW undergrad, Seth Ervin currently leads tech projects for the libraries in Charlotte. Phil Freeman, my room-mate from grad school, helps with city planning projects for the city. Last week Phil texted me to say the two of them got lunch and swapped stories. I hope that those stories were making fun of me, perhaps pointing out my weird habits. To hear this, it made me selfishly happy. To read this text, I nodded my head with approval, as my social world got slightly smaller in a time when I expect it to slowly fragment and become less cohesive.

I find myself at a place where I have no trouble meeting new people. I know hundreds of people on an individual basis---------but few of them know one another. I have lots of individuals as friends but it seems rare that they are part of a community that has any overlap. And this is why I was surprised to find out my friends Phil and Seth got up for lunch. It is a gift to have good friendships but it is even a greater thing to be a part of a group of inter-connected friends. The possibility of the three of us being friends starts a small community rather than just two separate friendships that I maintain on my own terms.

Yet seeing friends "overlap" like this is not the norm. My experience has lead me to expect fragmentation as the norm in the 21st century. But why do I expect this as the norm? UNC professor Zeynep Tufekci mentions larger cultural shifts that are pushing the social fragmentation:

“Social media’s rapid rise is a loud, desperate, emerging attempt by people everywhere to connect with each other in the face of all the obstacles that modernity imposes on our lives: suburbanization that isolates us from each other, long working hours and commutes that are required to make ends meet, the global migration that scatters families across the globe, the military-industrial-consumption machine that drives so many key decisions, and, last but not least, television---the ultimate alienation machine---which remains the dominant form of media.”

What stands out to me about Tufekci’s quote is that she suggests larger forces push us towards social media. We may imagine that our social media accounts are the root cause of weaker friendships and disconnected communities. In her 2012 article, Tufekci argues that social media has a small positive role in connecting people. That's not what she's saying. She is saying there are multiple factors such as suburbanization and the transient “migration” of Americans that is causing alienation and loneliness among Americans.

A Digital Integrated Community (A Quick Convenience for Transient Folks like Myself)

My favorite thing about Facebook(the one social media that I use on a daily basis) is the ability for me to have a digital, easy to manage contact with people I haven't seen in years. If I ever decide that I want to move to Raleigh or Seattle or even back to Thomasville(my hometown), I can just check Facebook to see if anyone I knew from my past lives there. It is our 21st-century phonebook. For me, I hope that in 15 years Facebook will still be a way for me to keep in touch for all the amazing people I've met in my life. In this way, Facebook can be a very helpful thing to people who are transient like me.

I live on the coast of North Carolina, which is 5 hours from Charlotte (where many of my friends live) and 4 hours from my hometown (where a majority of my family lives). I always go to the grocery store at night (when there’s no traffic and short lines) and I typically ride my bike (since it is about a 3-minute ride). And typically when I am looking up at the night sky as I ride home through empty streets in my small coastal town (with my backpack full of cheese, frozen blueberries, and steaks), I’ll think to myself “Why can’t I live closer all my old friends and family?” It is typically about 9:15pm when this happens.

As Tufecki suggests, we live in a world where family and friends are scattered across the globe. She’s right, we are migrants and we feel moments of alienation from place and people. But then, what do you do about that?

The design of the Facebook newsfeed is a great temporary fix for this. After I unload all of my groceries, I open up my Facebook to see a post of my friend Bobby who lives in Chad (Africa), pictures of my high school friend Michael and his wife who went to an 80’s party (Thomasville, NC), my friend Peter who was tagged in a photo (Scotland) and my friend James’s thoughts on a current politic controversy (New York City). While I felt alienated 20 minutes earlier, in a way, the Facebook newsfeed can give me the impression that I am in a “digitally integrated community.” By seeing all these far-flung friends on the same webpage in front of me, gives the impression that all these disparate people are “together.”

Facebook’s newsfeed makes sense of the multiple communities that I’ve been a part of, all in one place. I’ve lived in 6 different cities since I graduated high school. As exciting as it is to be someone who travels and meet new people, it can make one equally as anxious to realize that geographical location is more of a hindrance than you once imagined. To browse the profiles and posts of your friends pushes that reality out of my mind briefly. Yes, browsing profiles is an illusion of community, but for a moment it makes sense of intense fear of distance.

Could it be that browsing the recent posts of our friends is a sign of a healthy longing for our real-life segregated and geographically distant communities to integrate and make sense in the future? For myself, I say absolutely. Yes. This only brings forth more questions, which I've listed below. However, I am the kind of person who is deeply dissatisfied with social media as "community." That's not good enough for me. Social media creates possibilities for creating face to face connection, as Tufecki says in her article. It can have a role in creating face to face communities happen. Yet it is not the end experience, but the tool that can help create the real experience.

The question now is "What can I do to practically create community where I live, right here, right now? " This goes beyond just getting off social media. We've got to ask bigger questions-------many that I do not know of any certain solutions. But I do have 3 questions that I think could guide us in moving towards answers:

1.) Why is it that we want to make sense of the communities we’ve been a part of in the past? How do I make sense of all the communities I’ve ever been a part of?

2.) If 21st century Americans are migrant people, this means we must navigate the awkwardness of bringing different groups of people together. What are practical ways we can blend friend groups in the hope of creating new communities?

3.) It is possible to live in a place, but not personally invest in the place you live. How can we integrate ourselves into the places we live in right now?

How I Attempted to Blend Two Friend Groups in Charlotte

Here's my answer to the second question. What is a method for blending friend groups? My answer to that is this: intentionally introduce your friends who do not know one another. Find a way to create overlap in your community. This is easy to suggest but hard to practice. I'll share the story of the time I introduced my friends Phil and Seth a few years ago (who I mentioned earlier).

In May of 2016, I was in Charlotte for a community college conference. At the time, I'd met up for Phil for dinner after the conference and then I suggested "Hey man, why don't we swing by my friend Seth's house? You guys need to know each other." Phil's always open for meeting new people, so he said cook.

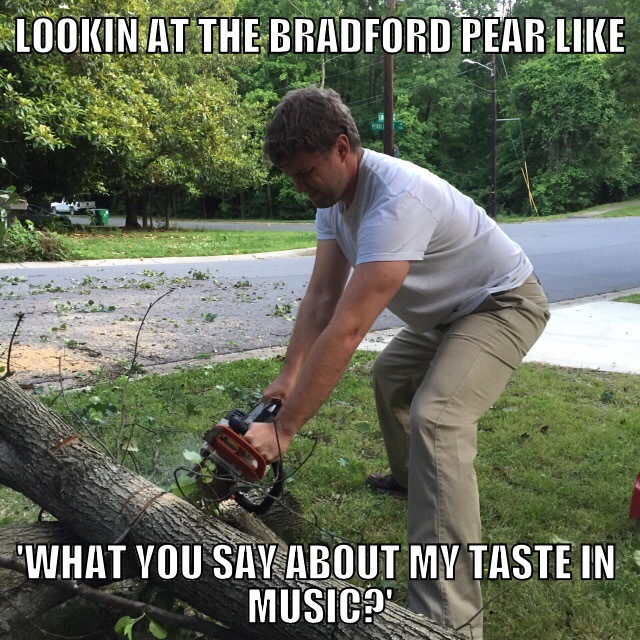

Phil had parked his car in Seth's driveway. We knocked on the door and Seth invited us into where his kids were eating dinner. I introduced the guys to one another and we stood in Seth's kitchen talking for about 2 minutes when we heard a loud crash outside. We all walked to the window to see a medium-sized tree had randomly decided to fall over and crash onto Phil's gray 2008 Honda Accord. We all paused for about 5 seconds just staring outside, asking each other "Did that hit your car?" Obviously, it did hit Phil's car. We walked outside quickly and when we approached the car------we saw that the Bradford Pear tree just landed perfectly across the hood of Phil's car.

Seth ended up borrowing a chainsaw from a neighbor. We then started the slow process of cutting up this tree so that we could salvage Phil's car. This "shared experience" became fun for me because I got to have a good time using a chainsaw. My attempt to merge friend groups had just resulted in about $500 worth of damage to my friend's car thanks to the choice of this big tree in Seth's yard. Phil's car had only been parked there for about 7 minutes before the Bradford Pear decided to fall.

Thankfully, in my case, I have friends with a sense of humor. Phil created the meme above out of the whole experience right after his car was destroyed. Trying to blend friend groups isn't always going to feel smooth and seamless like a Facebook newsfeed, Instagram story or even email. Real-life social interaction requires risks. This is much more awkward and unexpected than Facebook. I think I'm OK with that, since we now have the story about the time when Seth's tree smashed Phil's car.